Bassenge Photography Auction Held Dec. 3rd in Berlin

Modern and Contemporary Photography Auction at Villa Grisebach on November 26th in Berlin

Millon's Nov. 14th Auction Includes 19th and 20th-Century Master Photographers and Features Frédéric Barzilay's Work

Be-hold Schedules an On-Line Only Auction for Nov. 20th

380 New Items Posted up for Sale on I Photo Central Web Site in Just the Last Three Months

Photography Books: Conserving Color's Legacy and Cataloguing Paul Strand

Noted Swiss Photojournalist René Burri Passes Away at 81

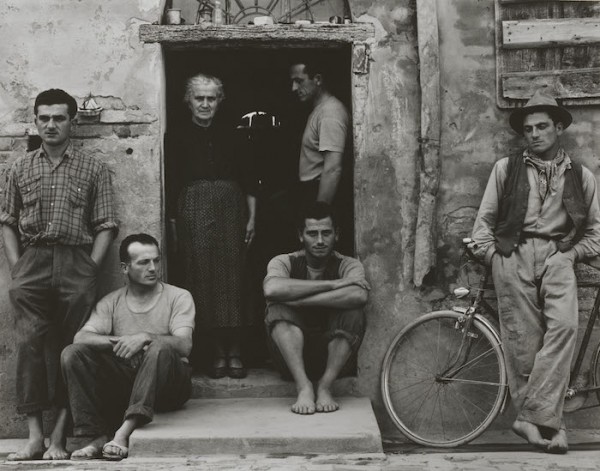

Paul Strand, Family, Luzzara (The Lusettis), Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Paul Strand Collection, purchased with funds contributed by Mr. and Mrs. Robert A. Hauslohner, 1972. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation

Paul Strand: Master of Modern Photography. At the Philadelphia Museum of Art, through January 4, 2015. The exhibition travels to Fotomuseum Winterthur, Switzerland, March 7-17, 2015; Fundacion MAPFRE, Madrid, Spain, June 3-Auguast 30, 2015; and Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK, March 19-July 3, 2016. For information: +1- 215-684-7860; http://www.philamuseum.org.

It's only fitting that the first major retrospective of Paul Strand's work in some 50 years is being mounted at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, a temple of modernism famously clad in classical architecture. The museum is where we come, after all, to ponder the most famous works of Duchamp, while the splendors of antiquity sparkle about us like elegant afterthoughts. Strand (1890-1976) is another perfect match for the museum, which recently acquired more than 3,000 prints from his archive, making it the largest repository of his work, and this sublimely straightforward survey pays worthy tribute to the master.

Strand was essentially a humanistic photographer; this is the message critics and curators glean easily enough from his later and most glorified work in Europe and Africa, where he sought to capture the nobility of daily life in peasant and tribal cultures. But he began as something of an avant-gardist, concerned as much with the camera's capacity for isolating and abstracting narrow glimpses of experience.

Thus, the exhibit, curated by Peter Barberie assisted by Amanda N. Bock, is a chronological thrust through a series of narrow, first floor galleries, offering each print at a perfect eye-level average. There isn't a lot of pedantic verbiage on the walls, nor is the optional audio tour concerned with dissecting every image. Strand is, after all, easy to look at and doesn't game the viewer. His early impulse toward abstraction is painterly and not drawn to expressionistic chaos. Under the influence of Albert Stieglitz, the young Strand's 1910 gum bichromate image of dried leaves and twigs in snow is a declaration of found beauty. And the angled geometry of sky and ridgepoles, or porch shadows in 1916 Connecticut evokes, smoothly enough, the vision of the Cubists. But his close-up portraits of artistic friends, their faces held askance from the camera, or in profile, suggest an even more modern, uncertain sensibility.

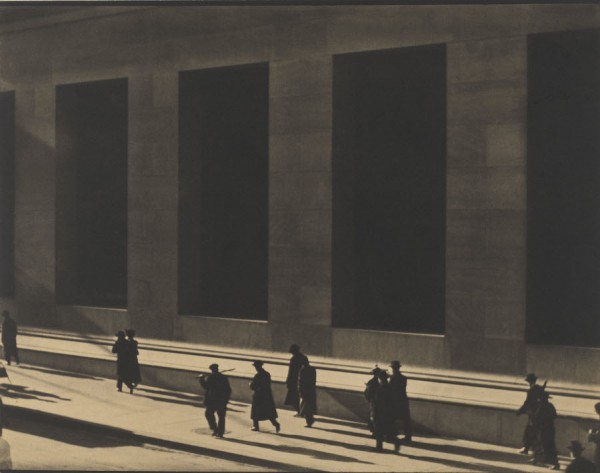

Paul Strand, American, Street, New York. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Paul Strand Retrospective Collection, 1915-1975, gift of the estate of Paul Strand, 1980 © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation

Soon, as Strand ventures famously into New York street photography, urban anxiety and grotesquerie emerge, and we can sense a change in aesthetic tone almost as if a stiff breeze cuts through the gallery. Here are the immortal images that spell Strand to us, in large measure, today: a blind woman wearing a "blind" sign, a yawning woman and a bearded man wearing a sandwich board, or shadowed souls trudging alongside the monolithic structure of the Morgan Trust Company on Wall Street. The unsentimental eye, the rigorous composition, the bold yet measured tonalities are all there, and it's worth venturing to the museum to get close to the luster of these gelatin-silver, palladium, and even some platinum prints.

Strand was an artist of his times, certainly, and much of his output hews to William Carlos Williams's poetic dictum, "No truth but in things." The cloudy, Stieglitzian impressionism was destined to move toward subtle, dark-toned close-ups of his Akeley motion picture camera, knotted vegetation, and architectural details, relieved to some degree by the up-close beauty of his portraits of wife Rebecca. But as the austere, rigorously focused Strand emerges from his early preoccupations and experiments, there's a dull sameness to shot after superbly rendered shot of the inanimate.

Thankfully, he never shut himself away, and the exhibition refreshingly connects the viewer to the tonic influence on Strand of the many painters from Stieglitz's circle--Georgia O'Keefe, Marsden Hartley, John Marin, Arthur Dove--who egged him on. By the 1930s, Strand was fully embracing film as an expressive outlet, and the PMA exhibit offers generous excerpts from his motion pictures: the 1921 "Manhatta," his first and a collaboration with photographer Charles Sheeler. It's a non-narrative work that is cited by the exhibition's curators as the first American avant-garde film, but is more of a poetic post-carding of New York local color.

There's more cinematographic life in Strand's muscular depiction of Mexican fisherman, "The Wave," with its beautifully composed stretches of boats and men struggling against the sea. By the 1930s, Strand's political engagement with leftist causes and unions was in full flower, but when the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor coincided with the release of his "Native Land," a film focused on union-busting from Pennsylvania to the Deep South, his political efforts were effaced by the war effort. He returned to still photography, which saved his career--indeed, the difficulties of making agit-prop motion pictures was likely to be a losing game.

Instead, Strand looked further outward, and in the 1940s, his celebrated picture books became a preferred form of presentation for his work. "Time in New England" famously collects people and places in a way that defined Yankee culture, from New Hampshire town halls to the craggy reserve of Vermonters. By 1950, though, Strand moved to France, avoiding America's anti-Communist wave, and it wasn't long before Europe breathed new life into his photography.

Paul Strand, Boy, Gondeville, Charente, France, Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Paul Strand Collection, purchased with funds contributed by Tom Callan and Martin McNamara, 2012. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation

As the exhibit traces, France yielded at least one Strand milestone: the 1951 image of a young boy in Charente, whose Gallic visage is an androgynous flag of nationhood that seems to evoke both Marianne, the feminine symbol of the French Republic, and Jean-Claude Belmondo. By 1953, Strand was in Italy, under the influence of the neorealist Cesare Zavattini, and it was in Italy that his most famous and perhaps his greatest photograph, of the Lussetti family, was realized.

The image, of the five grown Lussetti sons arranged in the doorway and on the porch of their peasant home, with their stoically beautiful mother at the off-center, is a justly celebrated masterwork of modernism. With typical painterly control, Strand posed these subjects, but their postures and expressions remain very much their own. The result is a landmark in naturalistic portraiture, and it's the legacy that many exhibition-goers will probably carry with them from the PMA gift shop (perhaps with the reproduction of the Charente youth).

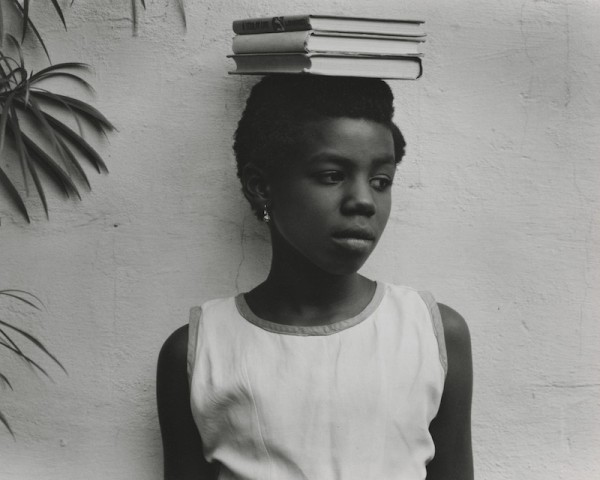

Yet the formality of Strand's European portraiture, still steeped in an Old World sensibility for all of its modernism, gave way most affectingly to a less controlled and more explicitly documentary style when he ventured to Africa in 1963, at the invitation of Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah, first president following the end of British rule. In Ghana, Strand saw something of the past careening toward the future: post-colonial subjects now free to join a modern world of political and cultural transformation. Again, Strand would pose some subjects indelibly--a Ghanian schoolgirl balancing books on her head in an echo of tribal water-carrying--but he would also let go, as his camera candidly chronicled the pure energy of tribal councils and the free-flowing life of a new Africa. One result was his final photography book, 1976's "Ghana: An African Portrait," a fittingly visionary capstone to a great career and a well-spent life.

Paul Strand, Attinga Frafra, Accra, Ghana, Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Paul Strand Collection, purchased with The Henry McIlhenny Fund and other Museum funds, 2012. © Paul Strand Archive/Aperture Foundation

The exhibition also concludes well, with an exhibit of Strand's Ensign reflex and Graflex cameras, and an Akeley movie camera, reminding us that there is, always, somewhat prosaic machinery behind the ineffable images of an immortal photographer. And the display also allows viewers to page through several of Strand's photography books via a digital flip-book display.

If anything, though, this faithful and coherent survey of Strand should not close the book on one of photography's legends so much as preserve the debate about photography's meaning. In her critical study, "On Photography," Susan Sontag relied on Strand's example to make point after point, noting that, "according to one critic, the greatness of Paul Strand's pictures from the last period of his life --when he turned from the brilliant discoveries of the abstracting eye to the touristic, world-anthologizing tasks of photography--consists in the fact that 'his people, whether Bowery derelict, Mexican peon, New England farmer, Italian peasant, French artisan, Breton or Hebrides fisherman, Egyptian fellahin, the village idiot or the great Picasso, are all touched by the same heroic quality--humanity.' What is that humanity? It is a quality things have in common when they are viewed as photographs." Sontag, ever the skeptic, wasn't blaming Strand for reductive philosophizing, but she was clear that Strand was an easy mark for cheap sentiment. This exhibit will make sure that taking his measure remains a complicated task.

Matt Damsker is an author and critic, who has written about photography and the arts for the Los Angeles Times, Hartford Courant, Philadelphia Bulletin, Rolling Stone magazine and other publications. His book, "Rock Voices", was published in 1981 by St. Martin's Press. His essay in the book, "Marcus Doyle: Night Vision" was published in the fall of 2005.

He currently reviews books and exhibits for both the E-Photo Newsletter and U.S.A. Today.

Bassenge Photography Auction Held Dec. 3rd in Berlin

Modern and Contemporary Photography Auction at Villa Grisebach on November 26th in Berlin

Millon's Nov. 14th Auction Includes 19th and 20th-Century Master Photographers and Features Frédéric Barzilay's Work

Be-hold Schedules an On-Line Only Auction for Nov. 20th

380 New Items Posted up for Sale on I Photo Central Web Site in Just the Last Three Months

Photography Books: Conserving Color's Legacy and Cataloguing Paul Strand

Noted Swiss Photojournalist René Burri Passes Away at 81

Share This